-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Martin Sprenger, Martin Robausch, Adrian Moser, Quantifying low-value services by using routine data from Austrian primary care, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 26, Issue 6, December 2016, Pages 912–916, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw080

Close - Share Icon Share

Background: Open debates about the reduction of low-value services, unnecessary diagnostic tests and ineffective therapeutic procedures and initiatives like „Choosing Wisely “in the USA and Canada are still absent in Austria. The objectives of this study are: (i) to establish a list of ineffective or low-value services possibly provided in Austrian primary care, (ii) to explore how many of these services are quantifiable using routine data and (iii) to estimate the number of affected beneficiaries and avoidable costs arising from the provision of these services. Methods: In May 2014, we identified low-value care services relevant for primary care in Austria. For our analysis we used routine data sets from the Austrian health insurance. All analysis refer to the insured population of the Lower Austrian Sickness Fund (n = 1 168 433) in the year 2013. Results: (i) We found 453 low-value services possibly offered in Austrian primary care. (ii) Only 34 (7.5%) services were quantifiable using routine data. (iii) In the year 2013, these 34 services were provided to at least 246 131 beneficiaries and the estimated avoidable costs arising were at least 11.38 million Euros. This accounts for 1.2% of overall spending of the Lower Austrian Sickness Fund for drugs and services provided by primary care doctors in the year 2013. Conclusion: The absence of a homogeneous, transparent and accessible coding system for diagnosis in Austrian primary care restrained our assessment. However, our study findings illustrate the potential utility and limitations of using claims-based measures to identify low-value care.

Introduction

A major goal of the 2013 health reform in Austria is to strengthen primary care by reorganizing care processes, through the monitoring of health indicators and the defining of quality standards.1 Although the reform aims to optimize provision of services to ensure safe and adequate care, health policy in Austria should foster an open debate about the reduction of low-value services, unnecessary diagnostic tests and ineffective therapeutic procedures.2 With these measures, patient safety and quality of care could be improved and will also preserve valuable resources that could be better utilised elsewhere.3 However, the polarizing political environment makes it difficult to start a rational public discussion about this issue. An initiative like ‘Choosing Wisely’ in the USA and Canada,4 ‘Smarter Medicine’ in Switzerland,5 the ‘disinvestment‘strategy in the UK started by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),6 ‘Slower Medicine’ in Italy, ‘Prescire’ in France and ‘Gemeinsam informiert entscheiden’ in Germany is still missing in Austria. At the moment only preliminary activities are underway.7

The aim of this study was to establish a list of ineffective or low-value services, which are possibly provided at the expense of the social health insurance in Austrian primary care. Moreover, quantification and estimation of services, avoidable costs and number of affected beneficiaries was performed.

Methods

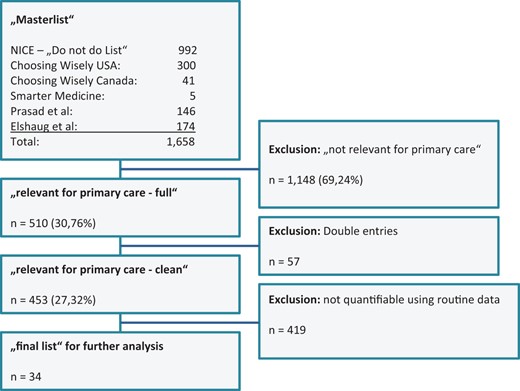

In May 2014, we merged the currently most important lists of low-value services; the ‘Choosing Wisely Lists’ from the USA8 and Canada,9 the ‘Do not do recommendations’ from NICE,10 as well as all ‘contradicted medical practices’ and ‘potentially low-value health care practices’ identified by Prasad et al.11 and Elshaug et al.12 into a list of 1658 questionable services. In the next step, three researchers (two general practitioners and one controller from the Lower Austrian sickness fund) decided independently and unanimously which of these services are possibly relevant for primary care in Austria. The majority decided which services were included (n = 510). The removal of double entries (n = 57) left 453 services for further analyses. 419 services had to be excluded because it was not possible to quantify them by using routine data. 374 (89%) due to the fact that no homogeneous, transparent and accessible coding system for diagnosis in Austrian primary care exists. The remaining 34 services were examined to estimate the avoidable costs arising from the provision of these services.

We used routine data from two main sources to quantify the avoidable costs arising from the provision of these 34 services. First the FOKO datasets (‘Folgekosten-Datenbank’) which are maintained by individual sickness funds to provide socio-demographic data on age, gender, occupation and income, as well as information on medication and therapeutic aids. Secondly, the LGKK datasets (‘Leistungswesen Gebietskrankenkassen’) which provide information on inability to work, sick days, benefits and other cost units. All analyses refer to the insured population of the Lower Austrian Sickness Fund (2013: n = 1 168 433) in the year 2013 (if not stated otherwise).

Comparison of services relevant for primary care in the master (n = 453) and final list (n = 34)

| Source . | Master list . | Final list . |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing Wisely Canada, July 20148 | 20 (4.4%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| Choosing Wisely USA, May 20149 | 116 (25.6%) | 8 (23.%) |

| Prasad et al. 201311 | 33 (7.3%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| NICE, July 201510 | 254 (56.1%) | 17 (50.0%) |

| Elshaug et al. 201212 | 29 (6.4%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Smarter Medicine, July 20145 | 1 (0.2%) | – |

| Summary | 453 (100.0%) | 34 (100.0%) |

| Source . | Master list . | Final list . |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing Wisely Canada, July 20148 | 20 (4.4%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| Choosing Wisely USA, May 20149 | 116 (25.6%) | 8 (23.%) |

| Prasad et al. 201311 | 33 (7.3%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| NICE, July 201510 | 254 (56.1%) | 17 (50.0%) |

| Elshaug et al. 201212 | 29 (6.4%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Smarter Medicine, July 20145 | 1 (0.2%) | – |

| Summary | 453 (100.0%) | 34 (100.0%) |

Comparison of services relevant for primary care in the master (n = 453) and final list (n = 34)

| Source . | Master list . | Final list . |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing Wisely Canada, July 20148 | 20 (4.4%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| Choosing Wisely USA, May 20149 | 116 (25.6%) | 8 (23.%) |

| Prasad et al. 201311 | 33 (7.3%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| NICE, July 201510 | 254 (56.1%) | 17 (50.0%) |

| Elshaug et al. 201212 | 29 (6.4%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Smarter Medicine, July 20145 | 1 (0.2%) | – |

| Summary | 453 (100.0%) | 34 (100.0%) |

| Source . | Master list . | Final list . |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing Wisely Canada, July 20148 | 20 (4.4%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| Choosing Wisely USA, May 20149 | 116 (25.6%) | 8 (23.%) |

| Prasad et al. 201311 | 33 (7.3%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| NICE, July 201510 | 254 (56.1%) | 17 (50.0%) |

| Elshaug et al. 201212 | 29 (6.4%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Smarter Medicine, July 20145 | 1 (0.2%) | – |

| Summary | 453 (100.0%) | 34 (100.0%) |

Overview of the final list of 34 services

| Diagnostic Tests (n = 9) . | Source . | Ineffectivea . | People affected . | Cost in € . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEXA scans more often than every 2 years. | Choosing Wisely Canada | y | 12 285 | 855 400 |

| Total or free T3 level when assessing levothyroxine (T4) dose in hypothyroid patients. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 34 444 | 564 128 |

| Atopy patch testing to diagnose IgE-mediated food allergy in primary care or community settings. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 5354 | 134 874 |

| Prostate-specific antigen testing. | Elshaug et al. | y | 13 383 | 92 739 |

| Pap smears on women younger than 21 years or who have had a hysterectomy for non-cancer disease. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 10 395 | 65 838 |

| Routine monitoring of bone mineral density after starting bisphosphonate treatment. | Elshauget al. | lower treshold | 262 | 8278 |

| Routinely monitored creatine kinase in asymptomatic people who are being treated with a statin. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Mammographic surveillance of women <29 years and 30–39 years at moderate risk and aged 30–49 years (>30% to beTP53 carrier) | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Routine monitoring for changes in bone mineral density in children and young people. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Drug interventions (n = 14) | ||||

| Long-term, frequent dose, continuous prescription of antacid therapy. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher threshold | 70 039/21 185 | 8 313 536/3 770 429 |

| Abatacept for the treatment of people with RA. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 78 | 555 267 |

| Homeopathic medications, non-vitamin dietary or herbal supplements as treatments or preventive measures. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 990 | 353 424 |

| Lipid-lowering medications in individuals with a limited life expectancy. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 6577 | 309 926 |

| Routinely prescriptionof of three or more antipsychotic medications concurrently. | Choosing Wisely USA | lower treshold | 222 | 273 129 |

| Oxycodone for pain. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 1128 | 230 095 |

| Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Prasad et al. | y | 1205 | 169 832 |

| Oxybutynin to frail older women. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 678 | 111 754 |

| Dehydroepiandrosteron (DHEA) in Women and DHEA or Testosterone in Men >65 years | Prasad et al. | y | 224 | 50 985 |

| Nicorandil to reduce risk in patients after an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 378 | 35 928 |

| Dapagliflozin in a triple therapy regimen with metformin and a sulfonylurea for treating type 2 diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 86 | 11 583 |

| Combination of a New oral anticoagulant (NOAC) with dual antiplatelet therapy in people who need anticoagulation, who have had an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 17 | 6612 |

| Routinely calcium channel blocker to reduce cardiovascular risk after an Myocardial infarction (MI). | NICE—Do not do list | lower treshold | 24 | 2160 |

| GHB for the treatment of alcohol misuse. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 13 | 1655 |

| Screening (n = 9) | ||||

| Routine screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher treshold | 2173/1421 | 37 488/24 511 |

| Routine annual cervical screening in women 30–65 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 83 686 | 1 343 421 |

| Cancer screening in adults with life expectancy <10 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 23 851 | 270 205 |

| Screening for gestational diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 4072 | 39 177 |

| Chlamydia screening in routine antenatal care. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Chlamydia screening in < 25-years old. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Pap smears in women <21 or > 69-years old. | Choosing Wisely Canada | n | – | – |

| Screening for hepatitis C virus in pregnant women. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Routine antenatal serological screening for toxoplasmosis. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Others (n = 2) | ||||

| Daily glucose testing in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients not using insulin. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 24 183 | 2 373 186 |

| Bladder instillations or washouts. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 498 | 5558 |

| Total (n = 34) | 296 245/24 6 131 | 11 377 133/16 216 178 |

| Diagnostic Tests (n = 9) . | Source . | Ineffectivea . | People affected . | Cost in € . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEXA scans more often than every 2 years. | Choosing Wisely Canada | y | 12 285 | 855 400 |

| Total or free T3 level when assessing levothyroxine (T4) dose in hypothyroid patients. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 34 444 | 564 128 |

| Atopy patch testing to diagnose IgE-mediated food allergy in primary care or community settings. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 5354 | 134 874 |

| Prostate-specific antigen testing. | Elshaug et al. | y | 13 383 | 92 739 |

| Pap smears on women younger than 21 years or who have had a hysterectomy for non-cancer disease. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 10 395 | 65 838 |

| Routine monitoring of bone mineral density after starting bisphosphonate treatment. | Elshauget al. | lower treshold | 262 | 8278 |

| Routinely monitored creatine kinase in asymptomatic people who are being treated with a statin. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Mammographic surveillance of women <29 years and 30–39 years at moderate risk and aged 30–49 years (>30% to beTP53 carrier) | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Routine monitoring for changes in bone mineral density in children and young people. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Drug interventions (n = 14) | ||||

| Long-term, frequent dose, continuous prescription of antacid therapy. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher threshold | 70 039/21 185 | 8 313 536/3 770 429 |

| Abatacept for the treatment of people with RA. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 78 | 555 267 |

| Homeopathic medications, non-vitamin dietary or herbal supplements as treatments or preventive measures. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 990 | 353 424 |

| Lipid-lowering medications in individuals with a limited life expectancy. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 6577 | 309 926 |

| Routinely prescriptionof of three or more antipsychotic medications concurrently. | Choosing Wisely USA | lower treshold | 222 | 273 129 |

| Oxycodone for pain. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 1128 | 230 095 |

| Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Prasad et al. | y | 1205 | 169 832 |

| Oxybutynin to frail older women. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 678 | 111 754 |

| Dehydroepiandrosteron (DHEA) in Women and DHEA or Testosterone in Men >65 years | Prasad et al. | y | 224 | 50 985 |

| Nicorandil to reduce risk in patients after an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 378 | 35 928 |

| Dapagliflozin in a triple therapy regimen with metformin and a sulfonylurea for treating type 2 diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 86 | 11 583 |

| Combination of a New oral anticoagulant (NOAC) with dual antiplatelet therapy in people who need anticoagulation, who have had an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 17 | 6612 |

| Routinely calcium channel blocker to reduce cardiovascular risk after an Myocardial infarction (MI). | NICE—Do not do list | lower treshold | 24 | 2160 |

| GHB for the treatment of alcohol misuse. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 13 | 1655 |

| Screening (n = 9) | ||||

| Routine screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher treshold | 2173/1421 | 37 488/24 511 |

| Routine annual cervical screening in women 30–65 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 83 686 | 1 343 421 |

| Cancer screening in adults with life expectancy <10 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 23 851 | 270 205 |

| Screening for gestational diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 4072 | 39 177 |

| Chlamydia screening in routine antenatal care. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Chlamydia screening in < 25-years old. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Pap smears in women <21 or > 69-years old. | Choosing Wisely Canada | n | – | – |

| Screening for hepatitis C virus in pregnant women. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Routine antenatal serological screening for toxoplasmosis. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Others (n = 2) | ||||

| Daily glucose testing in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients not using insulin. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 24 183 | 2 373 186 |

| Bladder instillations or washouts. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 498 | 5558 |

| Total (n = 34) | 296 245/24 6 131 | 11 377 133/16 216 178 |

*y, generally ineffective; n, not used.

Overview of the final list of 34 services

| Diagnostic Tests (n = 9) . | Source . | Ineffectivea . | People affected . | Cost in € . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEXA scans more often than every 2 years. | Choosing Wisely Canada | y | 12 285 | 855 400 |

| Total or free T3 level when assessing levothyroxine (T4) dose in hypothyroid patients. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 34 444 | 564 128 |

| Atopy patch testing to diagnose IgE-mediated food allergy in primary care or community settings. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 5354 | 134 874 |

| Prostate-specific antigen testing. | Elshaug et al. | y | 13 383 | 92 739 |

| Pap smears on women younger than 21 years or who have had a hysterectomy for non-cancer disease. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 10 395 | 65 838 |

| Routine monitoring of bone mineral density after starting bisphosphonate treatment. | Elshauget al. | lower treshold | 262 | 8278 |

| Routinely monitored creatine kinase in asymptomatic people who are being treated with a statin. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Mammographic surveillance of women <29 years and 30–39 years at moderate risk and aged 30–49 years (>30% to beTP53 carrier) | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Routine monitoring for changes in bone mineral density in children and young people. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Drug interventions (n = 14) | ||||

| Long-term, frequent dose, continuous prescription of antacid therapy. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher threshold | 70 039/21 185 | 8 313 536/3 770 429 |

| Abatacept for the treatment of people with RA. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 78 | 555 267 |

| Homeopathic medications, non-vitamin dietary or herbal supplements as treatments or preventive measures. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 990 | 353 424 |

| Lipid-lowering medications in individuals with a limited life expectancy. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 6577 | 309 926 |

| Routinely prescriptionof of three or more antipsychotic medications concurrently. | Choosing Wisely USA | lower treshold | 222 | 273 129 |

| Oxycodone for pain. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 1128 | 230 095 |

| Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Prasad et al. | y | 1205 | 169 832 |

| Oxybutynin to frail older women. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 678 | 111 754 |

| Dehydroepiandrosteron (DHEA) in Women and DHEA or Testosterone in Men >65 years | Prasad et al. | y | 224 | 50 985 |

| Nicorandil to reduce risk in patients after an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 378 | 35 928 |

| Dapagliflozin in a triple therapy regimen with metformin and a sulfonylurea for treating type 2 diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 86 | 11 583 |

| Combination of a New oral anticoagulant (NOAC) with dual antiplatelet therapy in people who need anticoagulation, who have had an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 17 | 6612 |

| Routinely calcium channel blocker to reduce cardiovascular risk after an Myocardial infarction (MI). | NICE—Do not do list | lower treshold | 24 | 2160 |

| GHB for the treatment of alcohol misuse. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 13 | 1655 |

| Screening (n = 9) | ||||

| Routine screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher treshold | 2173/1421 | 37 488/24 511 |

| Routine annual cervical screening in women 30–65 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 83 686 | 1 343 421 |

| Cancer screening in adults with life expectancy <10 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 23 851 | 270 205 |

| Screening for gestational diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 4072 | 39 177 |

| Chlamydia screening in routine antenatal care. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Chlamydia screening in < 25-years old. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Pap smears in women <21 or > 69-years old. | Choosing Wisely Canada | n | – | – |

| Screening for hepatitis C virus in pregnant women. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Routine antenatal serological screening for toxoplasmosis. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Others (n = 2) | ||||

| Daily glucose testing in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients not using insulin. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 24 183 | 2 373 186 |

| Bladder instillations or washouts. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 498 | 5558 |

| Total (n = 34) | 296 245/24 6 131 | 11 377 133/16 216 178 |

| Diagnostic Tests (n = 9) . | Source . | Ineffectivea . | People affected . | Cost in € . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEXA scans more often than every 2 years. | Choosing Wisely Canada | y | 12 285 | 855 400 |

| Total or free T3 level when assessing levothyroxine (T4) dose in hypothyroid patients. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 34 444 | 564 128 |

| Atopy patch testing to diagnose IgE-mediated food allergy in primary care or community settings. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 5354 | 134 874 |

| Prostate-specific antigen testing. | Elshaug et al. | y | 13 383 | 92 739 |

| Pap smears on women younger than 21 years or who have had a hysterectomy for non-cancer disease. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 10 395 | 65 838 |

| Routine monitoring of bone mineral density after starting bisphosphonate treatment. | Elshauget al. | lower treshold | 262 | 8278 |

| Routinely monitored creatine kinase in asymptomatic people who are being treated with a statin. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Mammographic surveillance of women <29 years and 30–39 years at moderate risk and aged 30–49 years (>30% to beTP53 carrier) | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Routine monitoring for changes in bone mineral density in children and young people. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Drug interventions (n = 14) | ||||

| Long-term, frequent dose, continuous prescription of antacid therapy. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher threshold | 70 039/21 185 | 8 313 536/3 770 429 |

| Abatacept for the treatment of people with RA. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 78 | 555 267 |

| Homeopathic medications, non-vitamin dietary or herbal supplements as treatments or preventive measures. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 990 | 353 424 |

| Lipid-lowering medications in individuals with a limited life expectancy. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 6577 | 309 926 |

| Routinely prescriptionof of three or more antipsychotic medications concurrently. | Choosing Wisely USA | lower treshold | 222 | 273 129 |

| Oxycodone for pain. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 1128 | 230 095 |

| Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Prasad et al. | y | 1205 | 169 832 |

| Oxybutynin to frail older women. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 678 | 111 754 |

| Dehydroepiandrosteron (DHEA) in Women and DHEA or Testosterone in Men >65 years | Prasad et al. | y | 224 | 50 985 |

| Nicorandil to reduce risk in patients after an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 378 | 35 928 |

| Dapagliflozin in a triple therapy regimen with metformin and a sulfonylurea for treating type 2 diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 86 | 11 583 |

| Combination of a New oral anticoagulant (NOAC) with dual antiplatelet therapy in people who need anticoagulation, who have had an MI. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 17 | 6612 |

| Routinely calcium channel blocker to reduce cardiovascular risk after an Myocardial infarction (MI). | NICE—Do not do list | lower treshold | 24 | 2160 |

| GHB for the treatment of alcohol misuse. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 13 | 1655 |

| Screening (n = 9) | ||||

| Routine screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. | NICE—Do not do list | lower/higher treshold | 2173/1421 | 37 488/24 511 |

| Routine annual cervical screening in women 30–65 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 83 686 | 1 343 421 |

| Cancer screening in adults with life expectancy <10 years. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 23 851 | 270 205 |

| Screening for gestational diabetes. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 4072 | 39 177 |

| Chlamydia screening in routine antenatal care. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Chlamydia screening in < 25-years old. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Pap smears in women <21 or > 69-years old. | Choosing Wisely Canada | n | – | – |

| Screening for hepatitis C virus in pregnant women. | Elshaug et al. | n | – | – |

| Routine antenatal serological screening for toxoplasmosis. | NICE—Do not do list | n | – | – |

| Others (n = 2) | ||||

| Daily glucose testing in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients not using insulin. | Choosing Wisely USA | y | 24 183 | 2 373 186 |

| Bladder instillations or washouts. | NICE—Do not do list | y | 498 | 5558 |

| Total (n = 34) | 296 245/24 6 131 | 11 377 133/16 216 178 |

*y, generally ineffective; n, not used.

Results

We found 453 possibly ineffective or low-value services relevant for Austrian primary care. Only 34 (7.5%) services were quantifiable using routine data. They split into four groups; diagnostic tests (n = 9), drug interventions (n = 14), screening (n = 9) and others (n = 2). Most of them are generally and evidently ineffective (n = 21), others should not be provided routinely (n = 5) and some services (n = 8) are not used in Lower Austrian primary care. Fourteen services (41%) exceed the cost of Euro 100 000. In total, these 34 services were provided to at least 246 131 beneficiaries and the estimated avoidable costs arising were at least 11.38 million Euros. When using the lower threshold for services that should not be provided ‘routinely’ the costs increase to 16.22 million Euros and the number of affected beneficiaries to 296 245. This accounts for 1.2–1.7% of overall spending of the Lower Austrian Sickness Fund for drugs and services provided by primary care doctors in the year 2013.

Discussion

This study provides, to our knowledge for the first time, quantification of the number of affected beneficiaries and estimates of cost to social health insurance through the reimbursement of potential low-value services in Austria. Aside from important findings, this study has some relevant limitations. Austrian primary care has no homogeneous, transparent and accessible diagnostic coding system. Therefore, only 34 (7.5%) out of 453 possibly low-value services could be assessed. This led to the exclusion of 374 (92.5%) potential costly low-value services from the data we analysed. Among them are imaging studies during the first 6 weeks in patients with non-specific low back pain, prescribing antibiotics for uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections or regular health checks in healthy adults. The total number may therefore be far greater.13 As some beneficiaries could be affected twice or more often, the frequency of performance of the 34 services analysed is not directly comparable with the number of beneficiaries affected. However, the number is high already and would increase significantly if more services could be analysed.

In the literature reviewed, we found only two studies using claims-based measures to identify low-value services. In 2009 Schwartz et al.14 analysed claims for 1 360 908 Medicare beneficiaries to assess the proportion of beneficiaries receiving these services, mean per-beneficiary service use, and the proportion of total spending devoted to these services. They found that 25–42% of beneficiaries were affected and constituted 0.6–2.7% of overall annual spending (depending on the method of analysis). The findings in this study are not directly comparable with ours as they build on other information (e.g. diagnosis), included other services and used other thresholds. The Washington Health Alliance15 took 11 measures defined by the Washington State Choosing Wisely Task Force and applied them to its database of 3.3 million beneficiaries in Washington state. A few findings are comparable to this study. For example that 4% of Washington female patients under the age of 21 received a potentially unnecessary Papanicolaou (Pap) test (7% in our study) and 57% aged 21–69 received unnecessary Pap tests (32% in our study).

Identifying low-value services is a complex and difficult task and the usage of existing and accepted lists is under critical debate. The Choosing Wisely lists for example, have been criticised for identifying low-impact and/or established low value services.16 In our study we could quantify a very heterogeneous group of services. Almost half of them exceed the cost of 100 000 Euro. Others didn’t exceed 10 000 Euro. Some affected more than 20 000 beneficiaries, some less than 100. Therefore, future research should refine our methodology to track overuse more accurately and allow prioritization, e.g. according to number of people affected, cost and/or chance to intervene.17

Translating different lists of low-value services into meaningful metrics that can be applied to available data sources was challenging. The term ‘routinely’ used in the recommendations is not very precise and our two thresholds, a lower one at 10% and a higher one at 25% affected beneficiaries, were chosen arbitrarily. Any change in cut off criteria would directly change the number of people affected and associated cost. Another imprecise term used in some of the recommendations is ‘individuals with a limited life expectancy’. Therefore we have chosen a pragmatic approach by subtracting 10 years from the average life expectancy at birth. Using the life expectancy at age 70 or 80 could be seen as more appropriate and of course resulted in lower cost. This is relevant for the use of lipid-lowering medications and cancer screening in individuals with a limited life expectancy. The value of some services depends on the clinical situation in which they are provided and administrative data often lack the necessary detail to distinguish appropriate from inappropriate use. An example is routine annual cervical cytology screening (Pap tests). According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists this test should not be performed annually in women 30–65 years of age. In the years 2012 and 2013, a Pap test was performed on 124 582 women. In total 83 686 women underwent the test twice and almost 10 000 women had it done five times (the maximum of tests was 15 times). The associated costs were Euro 1 343 421. Some of these women may have received an additional Pap test due to a positive or unclear test result. However, it is evident that Pap tests are performed too often in Austria and with shortcomings in smear taking and assessment.18

It is imperative that evidence-based recommendations are continually re-evaluated. We found two examples were the recommendations have not changed. According to the Canadian Rheumatology Association DEXA scans shouldn’t be repeated more often than every 2 years. For the period between the year 2011 and 2013 we found 12 285 people who had a repitition of a DEXA scan within 24 months. The associated costs were Euro 855 400. In March 2015 a Canadian group found eight evidence-based guidelines for DEXA scans in patients with osteoporosis or at risk for osteoporosis.19 All guidelines recommend intervals of two years or more. The second example is the NICE recommendation that atopy patch testing should not be used to diagnose IgE-mediated food allergy in primary care or community settings. In the year 2013, this test has been offered 6546 times to 5354 people. The associated costs were Euro 134 874. NICE did not change its recommendations and according to a recent review atopy patches lack specificity and sensitivity and may not be used to diagnose IgE-mediated food allergy.20

We found one example were the recommendation was not in line with the current evidence. According to NICE Abatacept was not recommended (within its marketing authorisation) for the treatment of people with rheumatoid arthritis. In the year 2013, this recommendation was still up-to-date and Abatacept has been offered 545 times to 78 people. The associated costs were Euro 555 267. In 2015, NICE updated it’s recommendations and the prescription of Abatacept and other biologicals are now approved under certain conditions.21

Finally, it is always difficult to transfer recommendations from one country to another. This is also true for compilations of low-value services. Therefore, it is necessary that Austria starts to discuss how its own national list of low-value services should be established. Additionally, to be successful in improving healthcare quality and efficiency in Austria, medical societies, academic institutions, consumer associations, health policy and the media need to work closely together to reduce ineffective and possibly harmful procedures and unnecessary waste of health care resources.

Conclusion

The absence of a homogeneous, transparent and accessible coding system for diagnosis in Austrian primary care restrained our assessment. However, our study findings illustrate the potential utility and limitations of using claims-based measures to identify low-value care. Future research should refine our methodology to define baseline and track overuse in Austrian primary care more accurately.

Key points

Low-value care is an important issue for Austrian primary care.

The estimation of affected people and avoidable costs requires an advanced data set.

Claims-based measures have several limitations to identify low-value care.

Austrian health policy should implement a homogeneous, transparent and accessible diagnostic coding system in primary care.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Lower Austrian Sickness Fund which allowed the analysis of routine data sets. The views represented are the views of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the Medical University of Graz or the Lower Austrian Sickness Fund. M.S. and M.R. designed the study and M.R. merged the low value lists. M.S., M.R. and A.M. decided independently which of these services are possibly relevant for primary care in Austria. M.S. primarily wrote the article, and all authors read and approved the final article.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Comments